Two years have passed since the last blogpost. Much has happened: authors must grieve the twin deaths of Alice Munro (May 2024), the poetic genius in short format, a writer of nostalgia for lives we never lived, and Paul Auster (April 2024), the textual illusionist, meandering through subjectivity and identity. If writers are distant friends, if books are their letters, must we not be sad at loss of such genuine correspondence?

Little must be written here, much elided over. Perhaps there will be time to return to Munro’s provocations, her controversial life and storytelling. Here, we have Auster: Auster who penned the private eye/I, the subjective singularity that engulfs his characters, his plots, his cities, his readers, him; Auster who was a kaleidoscope within his own stories of so many different personas: the Rothesque ghostwriter shadowing other artists, the archivist copiously chronicling his own cities through his own characters, the detective of imagined crimes, the seer and seen, the author and authored. To read Auster is to see New York differently, like it is to read Joyce and see Dublin differently. The mechanism, however, is different. Joyce presents a measured profligacy; Auster presents redundant minimality. Auster sees the world as if from a pinhole camera and then redoubles the blurry edges over, and over, and over, until the contours of a story emerge.

My relationship with Auster has been tenuous. I had always held him at a distance — his evocative premises, fixation on language and misinterpretation, error and frailty at odds with the scale of life I concerned myself with. Except, Auster beckoned me to look at the oddities even in this scale, in its repetitions, its frictions and its slippages. In the previous post, I had mentioned that I would implicate Auster when discussing our engagement with speculation. It is odd, remembering someone one day and finding them departed the next.

It is also odd to open an opinion piece on speculative fiction with literary fiction authors. Colour me biassed. I would love to speak of similarities in the mathematical worlds of Abott and Lem, of cultural distinctions that we routinely draw in these genres, of time and its evolution through time. But there are times when one must view the earth from the moon, when one must assay a country from another, when genres appear suddenly warped from another. That is the idea.

In his famed New York Trilogy,1 Auster speaks of truth, detection and detectives. Unlike conventional detectives, a Sam Spade, a Sherlock Holmes, a Miss Marple, characters whose shadow pervades the plot, whose larger-than-life identity provides solid ground on which you are willing to bet the truth, characters who linearise time: from not knowing to knowing, each chapter an increment, a nugget of wisdom, Auster’s detectives are diffuse, anonymous (and thus autonomous). There is a sense, in his works, that time is playing tricks on you, that the past will face you at the next intersection as your future, as your alter ego whose life is on a different trajectory.

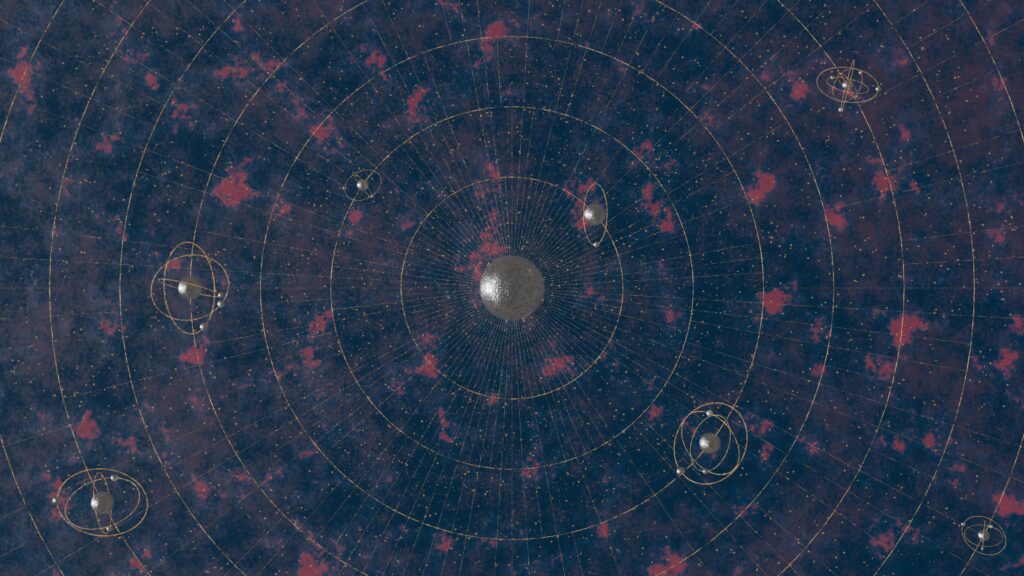

Strewn throughout his works, therefore, are indicators of an identity that do not cohere. A detective watches a mark even as he feels watched, a wretched cog in an absurd game of waiting, not acting. A horde of identities seem to erupt from the page: the detective, sometimes Daniel Quinn, sometimes Paul Auster (the character? the author? the pseudonym?) seem to speak simultaneously. A man involves himself with the life of Hector Mann, actor in silent movies, whose life on camera he brilliantly recalls in remarkable detail. Always, there is the idea that one life has been trapped by another, caught in a web, where in all directions what radiates is yet another strand of a life that one seems to be distantly living. Therefore of being under perusal from this distance, an inability to walk in your own skin as your own person.

In such a complex field, the ‘I’, argues Auster, is a sinkhole. It is at once the authoritative Investigator, the intimate Subject and the roving Private Eye, and the attractor for all such identities which entangles with yours. Through desire, through imitation, through surveillance and consumption, through comparison, the ‘I’ repeatedly contracts the other, measures up against it and then sinks it. I call this idea the ghost: a way of living that takes you on a collision course with somebody else’s life. As Brockmeier says: “It would take so little. Why didn’t it happen?”2

To live as a ghost is to live on the knife-edge of absolute subjection and absolute freedom, a curious phantasmic life indeed. It is a virtual unity of contradictions, a life where saying: how can I be other than what I eventually will be? is to simultaneously declare yourself free from the clutches of your own future. Every action is lent significance in the future; each passing desire, each obligatory act — are we not always susceptible to being looked back at in ten years, with a future us saying: this is not so; it was never meant to be so. Read Carloff (Time Heist), who writes about the present being continuously botched up by knowledge that things will reset. Or McCaffrey (Central Time), for whom the present is inundated with constraints. The horror of time is thrown open to us precisely when we let ourselves be determined by the future; should we not instead declare that the future will be what it will be, and thus declare ourselves free? An empty freedom indeed! But the ghost reminds us that all freedom is, in the final analysis, empty, a declaration sans creation.

Auster navigates through this subjection-freedom. There is always the terminus of what one must become; the end has always been in sight. What constitutes the story is the progression towards the end, the becoming of a pure subject, the possession of the body of the other, the ticking into pure freedom.

What does it matter to us? Here, let us return to Bachelard again who writes: “… the joy of reading is the reflection of the joy of writing, as though the reader were the writer’s ghost.”3 No reader, says Bachelard, reads without trying to become the writer. To the extent that a modest reader is kept in place is by the sheer genius of the writer himself. The good writer maintains a ghostly reader, there to be possessed but resisting possession. She is the hero of every horror genre who keeps the ghost at bay, who resists every attempt on her body, on her soul. The reader, in his turn, must attempt a seizure, a subjection-freedom, a possession; that is the fulfilment of his desire.

In this curious setting, Bachelard hints at an equally curious idea. Who here is creative if not the reader? The writer, through the text, is present as if objectively. It is the reader who must move the text and be moved by it in turn. It is his gaze, his experience of the text, that is Bachelard’s central concern. The writer is relegated to the margins, the significant other. This is an inverted horror movie, one where we enter the lives of the ghosts and see them haunting the real world. The selection by the reader is the artistic act, insofar as art is the experience of expression of desire.

Through Auster then, we find what it is to be a hungry artist, continuously trying to meld with the world. In the pieces that we shall publish this year, especially the entries from our Faux Tales contest, this is what we have continuously tried to do. Which story among these would I have written; who is the author we would have anyway become if we were to become the Author?

There is, of course, a silly way of reading this entire idea as hubris. Are we therefore saying that we could have written the story in spite of the author? Are we not therefore saying that the author is a mere accident, a chancy being who got there first, planted their flags on terrain that was otherwise our manifest destiny? This is not what I mean by the ghost. The ghost does not exist without man, the reader without the writer, the editor / magazine without our authors. In the absence of the author, there is no future that we can emptily gesture towards. It is only when our authors write these stories that they bring into the world the conditions of our freedom; it is only by pointing at them, their expression, their words, that we say: there, that is exactly what I would have wanted to say anyway. There is no predestination because there is no future yet — the future will be in its own time — there is only a freedom from the future that we seek.

Consider, in this vein, Vajra Chandrasekera’s comments (The Limner Wrings His Hands) on the author-machine. Begin reading where it allegedly ends: “This story was generated by the machinic state, the prison within the prison like the text within the text, the state of the machine, the machine ulcerated, the machine cold but learning… To fight gods, especially gods that you made, you must become monstrous.” End where he begins: “This story is a monster; that is to say, this story is written by a monster. That is, that is to say, a monster is a mantra, a maniac, a (de)monstration, a (demon)stration, a(n auto)maton, a matos, an emanation of the manas.” In between, you might find him saying that the author-artist does authorship-artistry only when throws open his own subjection to the universe, only when he absolves his own subjection. Art here is not unlike faith: the artist does not make a spectacle of the prison; he short-circuits the transition between the reading of the prison and the finding oneself within it. This is the artistic function.

This is also a lesson in temporal intimacy, a coming together at every moment of our anticipation for tomorrow. Call it what you will: a textual tryst, a speculative romance, a political solidarity; these are but labels of a gnawing metaphysics of time. And it requires other intimacies, some cultural, some genetic, some interactional. The question then is who or what emerges from these intimacies, and whether such emergence may be truly called South Asian. What are the peculiarities of South Asian speculative fiction, and is there some truth to South Asian experiences that can serve as a criterion for categorizing stories?

In time, I will write about this.

Notes